Staff Writer

COMMAND Agriculture, which was used as a vehicle for massive looting by political elites and their cronies, was only scrapped in name.

In reality, the government continues forking out millions of US dollars to settle the loans of defaulting farmers whose cumulative debts are now being inherited by long-suffering taxpayers.

When taxpayers are forced to inherit up to 84% of government-guaranteed US dollar agricultural loans, the time is long overdue for sober reflection.

Independent economists say the government’s agricultural financing model is problematic as it burdens taxpayers with the debts of farmers who are defaulting on state-guaranteed loans.

The country’s rising debt could soon force the government to sell some state-owned enterprises to raise funds for debt repayment.

Looting was rampant under the controversial Command Agriculture programme — with a parliamentary committee reporting that it saddled Zimbabwean taxpayers with a US$1.6 billion debt. The bleeding continues, six years after the name of the scheme was changed to deflect public scrutiny.

Loan delinquency by beneficiaries of government-guaranteed agricultural loans is scandalously high, marking a

continuation of the shoddy management of public finances.

The government changed Command Agriculture’s name to National Enhanced Agriculture Productivity Scheme (Neaps) and announced that agricultural financing was now being handled by the private sector with effect from the 2019 farming season.

But the bleeding continues unabated, with Treasury issuing bank loan credit guarantees which have ramped up the taxpayers’ exposure to defaulting farmers.

Command Agriculture has been a scandalous use of public funds, with no tangible benefit to the nation, while the financing cartels have pocketed hefty profits. The scheme has been characterised by a lack of fiscal prudence and a distortion of farmers’ access to credit. Far from shoring up food security and macro-economic resilience, it has accentuated the country’s vulnerabilities to hunger, poverty and the climate crisis.

Funding under the re-named Command Agriculture (Neaps) scheme is handled by CBZ Bank and the Agriculture Finance Corporation or AFC (formerly Agribank). These two financial institutions are lending to farmers under government guarantee.

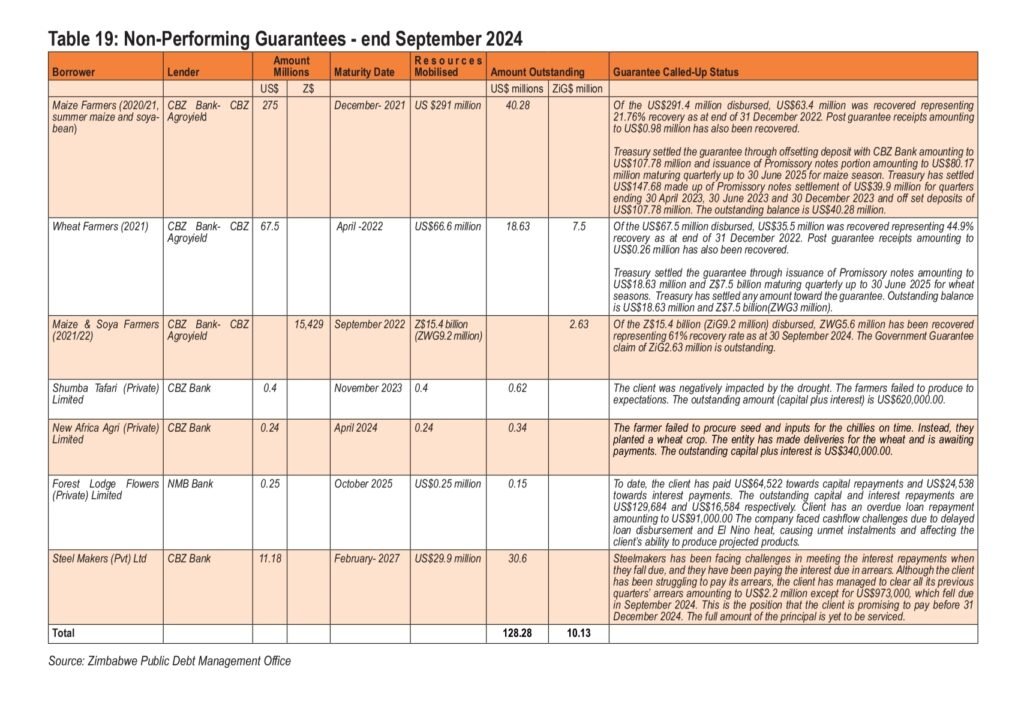

The latest Public Debt Statement presented to Parliament by Finance minister Mthuli Ncube shows that farmers are continuing to default on their loans (see table below). The debts will ultimately be inherited by taxpayers.

Taxpayers are in trouble

Of the US$291.4 million disbursed to farmers for maize and wheat production in the 2020/2021 summer cropping season, only US$63.4 million was recovered. This represents a 21.8% recovery rate.

Treasury settled its guarantee obligations through an offsetting deposit with CBZ amounting to US$107.8 million and the issuance of promissory notes totalling US$80.17 million which are envisaged to mature quarterly up to 30 June 2025. Treasury has settled US$147.68 million related to these loans, leaving an outstanding balance of US$40.28 million.

In 2021, US$67.5 million was disbursed to wheat farmers under the CBZ Agroyield scheme. Of this amount, only US$35.5 million was recovered, representing 44.9%. Treasury settled the amount through promissory notes totalling US$18.63 million and ZW7.5 billion which is envisaged to mature quarterly up to 30 June 2025.

The bleeding continues

In terms of contingent liabilities [potential financial obligations], the government issued guarantees amounting to US$24.5 million to the Agriculture Finance Corporation during the period from January 2024 to September 2024 for the funding of the 2024 winter wheat season.

It has to be remembered that the key mandate of AFC Holdings — which is wholly owned by the government — is to champion sustainable agricultural financing and development. But how sustainable is the Neaps scheme which has become a feeding trough for farmers who default on loans that are then inherited by taxpayers?

Debt crisis…Finance minister Mthuli Ncube conceds that Zimbabwe has a serious debt problem.

The thorny question is: What measures is the government adopting to stem the loss of public funds? In the Public Debt Statement submitted to Parliament on 28 November 2024, Finance minister Ncube proffered an unconvincing solution:

“Government is managing the risk of default by beneficiaries of guarantees by monitoring their performance against the terms and conditions of the borrowing to ensure timely debt servicing. With this policy, defaulting borrowers will not be considered for guarantees for future projects. All guarantees are approved by the External and Domestic Debt Committee (EDDC), in line with the Public Debt Management Act.”

It is not enough to merely slam the door in the faces of defaulting borrowers; the government must explain the practical measures it is taking to recover the outstanding money. Taxpayers should not be burdened with the private loans of delinquent borrowers. The moral hazard is self-evident.

Fuelling public debt

Zimbabwe is in serious debt distress, with the total debt stock soaring to US$21.1 billion as of December 2024, up from US$18bn in December 2022.

Presenting the 2025 National Budget on 28 November 2024, Finance minister Ncube conceded the country’s debt problem.

“Public debt and debt servicing obligations have increased sharply, following the assumption of RBZ liabilities by central government, including blocked funds. The increased government financial needs have led to painful trade-offs as some fiscal outlays for developmental and social expenditures have been crowded out to accommodate the additional expenditures on debt servicing and unbudgeted expenditures,” said Ncube, acknowledging the burden particularly imposed by Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe legacy debts which have been inherited by taxpayers. Although he did not say so, some of these debts emanate from agriculture-related looting.

The country’s debt burden has become unsustainable, forcing the government to appoint former Mozambican president Joaquim Chissano to facilitate a debt resolution dialogue. African Development Bank president Akinwumi Adesina is champion of the arrears clearance and debt resolution process.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa flanked by the champion of Zimbabwe’s debt resolution process and African Development Bank president Akinwumi Adesina (left) and the dialogue facilitator and former Mozambican president Joaquim Chissano (right) during discussions in Harare. Picture credit: Office of the President and Cabinet.

The debts contracted by the government tend to be odious, benefitting a few people at the expense of the citizenry. The government has scandalously offloaded many of the debts onto the shoulders of taxpayers without fully disclosing the defaulting individuals and companies, placing the burden on citizens who are already suffering from decades of economic decline.

The recovery rate for on-lent loans and guarantees issued for agricultural support is very low. Politically exposed persons who perennially benefit from government schemes have developed a habit of not paying back their loans.

They received expensive equipment under the Farm Mechanisation Programme, but did not bother to pay back. As a result, the government in 2015 assumed a US$1.5 billion debt which was part of the non-performing loans to politically exposed individuals who received loans under the US$200 million Farm Mechanisation Programme. The taxpayer must ultimately foot the bill.

This is not the only agriculture-related debt. In 2019, the government agreed on contingent liabilities of US$3.5 billion by way of compensation owed to former commercial farmers who were affected by the fast-track land redistribution programme at the turn of the millennium.

Apart from the multi-billion-dollar Global Compensation Deed, hundreds of millions of dollars will go towards compensating 94 European farmers whose land was expropriated in violation of Bilateral Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements (Bippas).

The International Monetary Fund says Command Agriculture — renamed Neaps — is not only fraught with risks but also lacks transparency.

“Although the input financing under the Command Agriculture programme was transferred to the banking system under a risk-sharing arrangement, risks to the (national) budget remain as the government provides an 80% credit default guarantee,” the IMF noted.

In a week’s time, the IMF is expected to dispatch a technical team to Harare to commence a Staff-Monitored Programme (SMP).

Desperate to achieve macro-economic stability, Harare requested an SMP, which is expected to shed light on Zimbabwe’s often-inconsistent economic policy. An SMP is an informal agreement between an IMF member country and the international financial institution to monitor the member country’s economic policies.

In the aftermath of previous staff-monitored programmes, the IMF has often expressed concern over the government’s shortcomings, notably in policy implementation.

Can new title deeds unlock financing?

The government recently appointed a Land Tenure Implementation Committee chaired by Zanu PF oligarch Kudakwashe Tagwirei. The committee is facilitating the issuance of title deeds to farmers.

Tagwirei has told state media that when a farmer takes out a bank loan, the farmland will remain the property of the state. But on the other hand he asserts that banks will be able to offer loans on the back of these title deeds.

As it turns out, if the farmer defaults on the loan, the bank cannot proceed to seize the land. Instead, the financial institution must sit down with the government with a view to finding a solution. This may entail re-allocating the farm to another Zimbabwean who does not already own land.

A question inevitably arises: If the banks cannot seize land which has been used as collateral, then how bankable are these so-called title deeds and why should financial institutions put depositors’ funds in peril by lending to defaulting farmers?

Please read also: Special Investigation: The forgotten scandal— Still no forensic audit into Command Agriculture